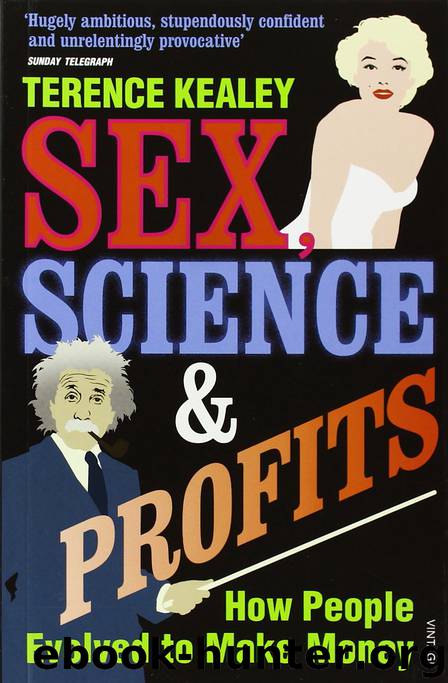

Sex, Science And Profits by Terence Kealey

Author:Terence Kealey [Kealey, Terence]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Random House

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

CHEMICALS

Let me consider one more of Britain’s mythological ‘failures’, that of the chemical industry. The conventional view was stated by Professor Denis Noble of Oxford University: ‘The first major government intervention in science in the UK, in 1913, was to save a nation approaching a state of war with a country on which we had become almost totally dependent for chemical products.’11

By 1913 Germany accounted for 24 per cent of the world’s chemical output, and the USA, with its much larger population, 34 per cent, but Britain accounted for only 11 per cent. The outbreak of war in 1914 did, indeed, find Britain alarmingly exposed chemically. Britain had grown dependent on Germany for many chemicals, not least the khaki dye for its soldiers’ uniforms, and 1914–18 witnessed desperate shifts as British chemists and industrialists struggled to provide matériel.

Yet criticisms of the British chemical industry are, curiously, hard to sustain. First, the chemical industry grew faster between 1881 and 1911 than any other industry in Britain except for public utilities, and by 1911 it was employing 2.7 per cent of the manufacturing labour force.12 Britain did well in detergents, paints, coal tar intermediates and explosives (explosives are useful in war). The British chemicals industry, therefore, cannot be criticized for not growing, only for not growing as fast as Germany’s. This must be a general criticism because nobody – neither the USA, nor France, nor Belgium, nor the Netherlands – expanded into chemicals, especially organic chemicals, like Germany. Moreover, Britain soon learned its strategic lesson. During the First World War it created the British Dyestuffs Corporation, which in 1926 combined with Nobel Industries, Brunner Mond and the United Alkali Company to create ICI, the chemicals giant that by the late 1930s was employing nearly 500 research scientists and many of whose managers were scientifically trained. Chemically, Britain was fully prepared for war in 1939.

British chemical companies made mistakes, of course. Specialist historians complain that Britain’s United Alkali Producers retained for too long the Leblanc process for synthesizing sodium carbonate, when it should have shifted more of its production into its licensed Solvay process after 1897. But it can be difficult to scrap profitable technology for untried technology. Consider Britain’s electronic industry. This, too, is often criticized, but for the opposite offence, namely for an overenthusiasm for new technology. The major British electronic company, GZ de Ferranti, was obsessed by new technology, and Ferranti always installed it, even if the older technology was more profitable or more reliable.

However, these individual mistakes are small when put into context. United Alkali Producers’ mistake over the Leblanc process cost it around £1.9 million,13 yet the company still prospered, and if one episode of a forgone £1.9 million can be described as one of the worst examples of British ‘entrepreneurial failure’ before 1914, there could not have been much wrong with the British entrepreneurialism of the day.

The Germans excelled in organic chemistry only for the same reasons they excelled in iron and steel – the government poured vast funds into technical schools, universities and scientific research.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7303)

A Journey Through Charms and Defence Against the Dark Arts (Harry Potter: A Journey Through…) by Pottermore Publishing(4796)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4571)

A Journey Through Divination and Astronomy by Publishing Pottermore(4375)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4118)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3679)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3616)

Alchemy and Alchemists by C. J. S. Thompson(3506)

Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre(3417)

Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker(3363)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3352)

Inferior by Angela Saini(3310)

A Mind For Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra) by Barbara Oakley(3293)

Origin Story by David Christian(3191)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3172)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3123)

The Elements by Theodore Gray(3048)

A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking(3017)

A Journey Through Potions and Herbology (A Journey Through…) by Pottermore Publishing(2843)